Ivy

Hedera helix

According to Gipsy folklore, Ivy leaves were used to hide the baby Jesus from King Herod’s men during the Massacre of the Innocents. And although originally a plant heavily associated with mid-winter pagan traditions, the evergreen Ivy (like Holly) became a Christian symbol of life and immortality.

Initially though, in the early days of Christianity, the clergy tried to give Ivy with its links to paganism a reputation for being unlucky, forbidding the cut leaves from being brought into church buildings. But the smear campaign failed. Maybe people found all the greenery cheerful during the cold stark days of winter or maybe the everlasting life metaphor just struck a chord. Whatever the reasons, Ivy has now been used in Christmas decorations for centuries. In his book ‘A Survey of London’, (1598), John Stowe included an account of Christmas that he’d come across from 1444:

“Against the feast of Christmas every man’s house, as also the parish churches, were decked with holm (holly), ivy, bays and whatever the season of the year afforded to be green. The conduits and standards in the streets were likewise.”

Then, after the festivities, the cut foliage was often fed to sheep and other livestock when fresh green fodder was scarce. Waste not want not.

Ivy was also associated with the Bacchus, who is generally portrayed wearing an ivy wreath. So on the one hand Ivy was a Pagan turned Christian symbol of eternal life, on the other it was associated with the Roman God of agriculture, wine-making, drinking, fertility and ritual madness. And to be honest, trying to understand the etymological origins of ‘Ivy’ can make you feel you were going a little crazy too.

Most of the etymological dictionaries agree that the word ‘Ivy’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon word ’Ifig’ via ‘Ivvy’, and that that the Anglo-Saxon word ‘Ifig is of “obscure origins”.

But R.C.A. Prior MD, the writer of ‘On the Popular Names of British Plants’ (1879), disagreed. He looked further back to Ancient Rome and Classical Greece for the word’s origins, and uncovered a varied and complicated history that it seems even he found difficult to get his head entirely around. His lengthy entry under Ivy’ begins:

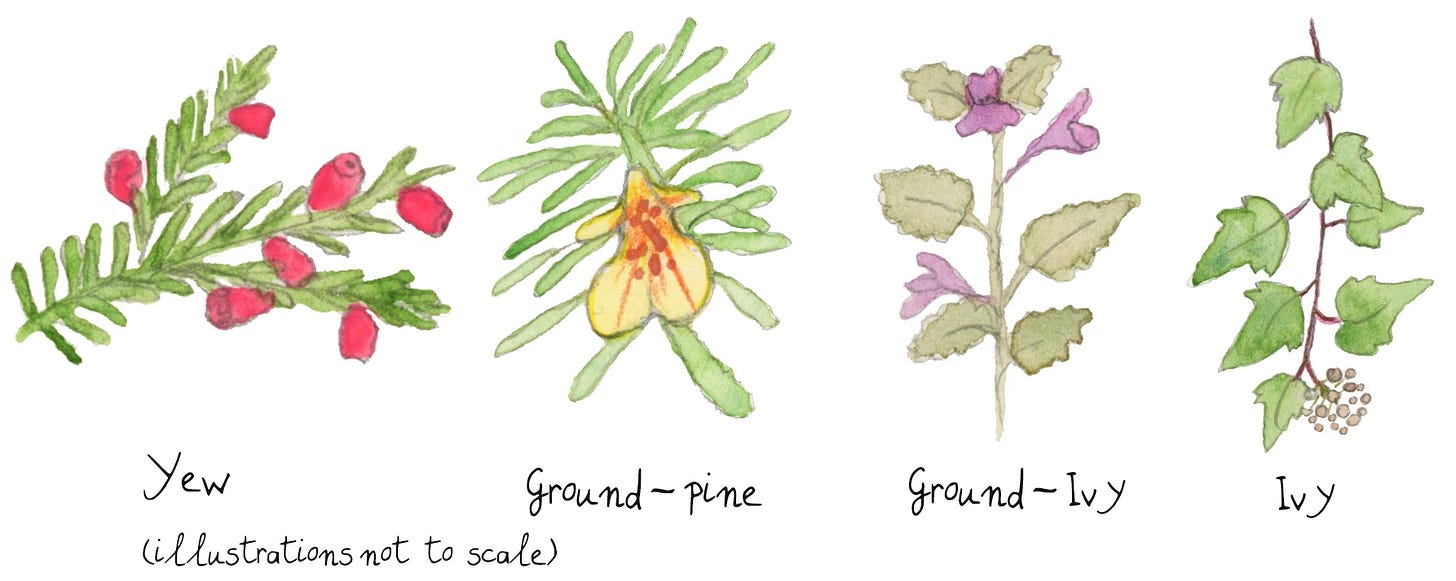

“a word strangely mixed up with the names of the yew tree.”

He wrote that it was beyond doubt that the words for Ivy and Yew were the same - in the different languages of Europe - and that this came about as a result of at least one Roman copying error. He explains that in English ‘Ivy’ comes from ‘Iva’, and ‘Yew’ from (what he described as) the same word, written ‘Iua’. There are references to ‘Ground Pine’ and ‘Ground Ivy’; ‘Hedera terrestris’ (a no longer valid scientific name given to Ground-Ivy) and ‘Hedera helix’ (Ivy) - though it’s not always clear (to this brain anyway) how it got confused.

Despite being convinced that Ivy and Yew came from the same source, Prior still had trouble determining how the word became attached to the different plants. In trying to make sense of it, he includes references to Pliny, Chaucer, Aubrey, Parkinson and others; he describes how along the way, there were abbreviations of misspellings, while mentioning numerous plant names in various languages from Greek and Latin (of different ages) to more modern European tongues.

It is not an easy read. I arrived at the end of Prior’s 759 word discussion with a feeling I’d strayed into an area of etymology well beyond my pay grade and with a clearer understanding as to why so many etymologists over the centuries, when tackling the history of the plant name ‘Ivy’, had gone for the easier conclusion of “obscure origins”.

Re-reading Prior’s text didn’t much improve my understanding of it, but it did remind me of Ivy’s Bacchanalian associations as, after the second or third attempt, I was beginning to need a drink.

Ivy’s link with Bacchanalian revelry lasted well into more recent centuries when ivy leaves were often draped over the entrances to taverns as a sign that good liquor was to be had inside.

Ivy has other links with alcohol. Maud Grieve wrote in 1931 that the ancients tied Ivy leaves to their brows to prevent them from getting drunk. She also tells us that those same ancients wrote that boiling a handful of gently bruised ivy leaves in your wine prevented intoxication.

Bacchus impersonations or Ivy flavoured wine. Not an easy choice.

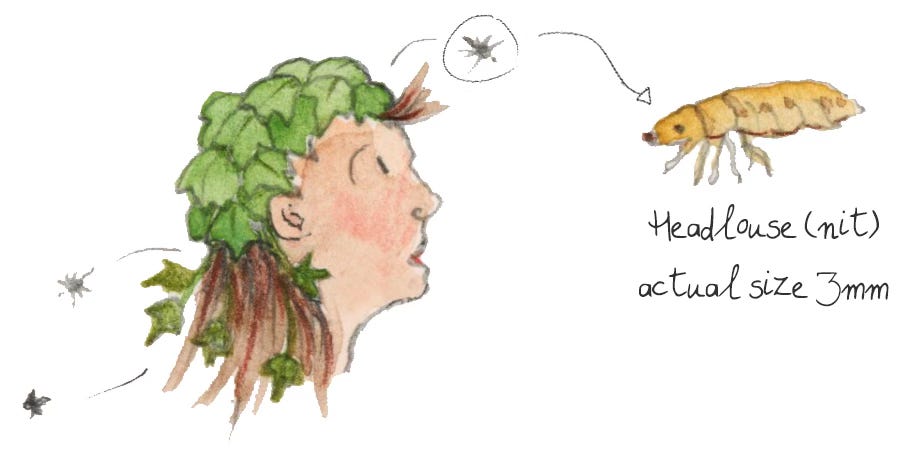

Tying Ivy to your head apparently had additional - and sometimes contradictory - effects. In 1912 Ella Leather writes in ‘Folklore of Herefordshire’, that a cap of Ivy leaves stops your hair falling out. However, three hundred years earlier, John Gerard (1545–1612) claimed the opposite:

“the gum that is found upon the trunke or body of the old stock of Ivie, killeth nits and lice, and taketh away haire.”

D.C. Watts Dictionary of Plant-Lore explains how Ivy is useful in many areas, from Yuletide health predictions to preventing illness in cattle. And it was eventually considered an effective way of stopping witches entering churches - the priests’ claim that it was unlucky well and truly reversed.

Both parts of the scientific name refer to the way in which the plant grows. ‘Hedera’ traces back to the Latin word ‘prehendo’, which means “to grab” and ‘Helix’ meaning ‘spiral’.

Other names for Ivy are: Bentwood, Bindwood, Ivery, King’s Choice Ivy and Lovestone

Flowerology is a reader supported publication. To support my work you might consider to subscribe for free,

buy me a tea (to keep me awake when reading ancient herbals and plant-lore till deep in the night)

or simply click the heart shaped ‘like’ button on the top or bottom of this post (it helps the algorithms apparently). Thank you so much!

If you’re curious about other wildflower names, you can find all flowers covered so far in Flowerology in the alphabetical archive. And you can find a list of all the books used for researching Flowerology in the Reading List which is frequently updated with new etymology dictionaries, herbals and plant lore books.

This newsletter is NOT a field guide for flower identification. It’s often difficult to tell the difference between harmless plants and poisonous plants and some flowers are rare and protected by law, so, NEVER pick or use any plants or flowers if you’re not sure about them.

illustrations and text ©Chantal Bourgonje

Is it true that ivy is (mildly) toxic and leads to vomiting? That would explain why/how it helps avoid getting drunk 🤭

In my garden it grows and grew all over the pace. I have been removing a lot of it. Of course you know the Dutch name: klimop. No misunderstanding there 😊

"Het is voor kabouters om op te klimmen' zei een jongetje een keer tegen me. Heerlijk!