Comfrey

Symphytum Officinale

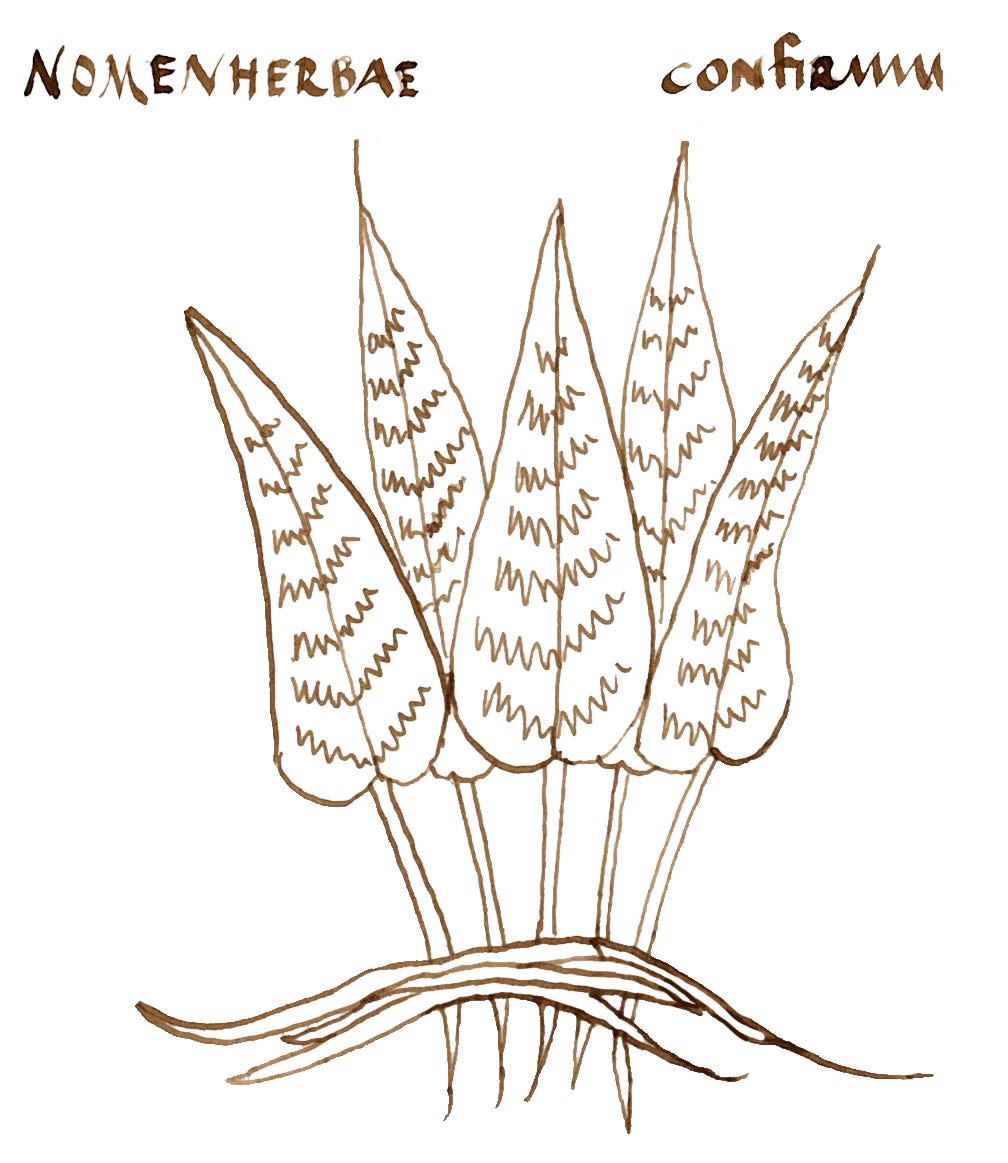

One of the oldest Herbals that mentions Comfrey is the Herbarium of Psuedo-Apuleius1 which describes, with illustrations, 131 medicinal plants, and was compiled in the 4th century from Latin texts. Chapter 59 of the Herbarium is dedicated to Comfrey, which was then called Confirma, from the latin word Confirmare meaning to ‘bind together’. Amongst various medicinal uses, it describes how its name and healing powers could be “proven” by boiling 2 pieces of beef together with 2 pieces of Comfrey root in a large pot. The beef would bind together as if it were one piece.

Fast forward a few hundred years and Comfrey, or Cumfiria in Middle English, appeared in many herbals for the healing of bones.

Not by boiling the poor patient’s body parts with Comfrey, but by pounding the root to a slimy pulp, wrapping the broken bone in leather while covering the leather inside and out with the pulp. When dry, the Comfrey Root pulp would harden and create a solid cast. D.C. Watts writes in his Dictionary of Plant Lore, that it would work even better, if you chanted the following 3 times when applying ‘Cumfiria’:

“Our Lord rade, The foal slade, Sinew to sinew and bone to bone In the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit”

Even more powerful healing occurred if you used the pink flowered Comfrey for men and the white flowered Comfrey for women. So pink hasn’t always been considered a girly colour - or at least not when its comes to mending broken bones.

It was said that the Crusaders took Comfrey, which they called ‘Wound Wort’, with them to the holy land, in case bones were broken and flesh wounds suffered during combat. Another theory claimed that the practice of using comfrey on wounds was brought back to Europe from the Middle East, which may well have been the case as it was also known as ‘Saracen’s Wort’.

The Scientific name Symphytum traces back to the Greek word ‘Sumphuo’ which means ‘to grow together’ and again refers to the wound and fracture healing properties of Comfrey. In addition to healing wounds and sores and other skin ailments, Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) suggested Comfrey could be used for liver problems, a paste being made up of Comfrey, boiled hawk’s lung, Hemlock, butter made in the month of May, and applied to the sufferer’s side. Hildegard warns against eating Comfrey if there’s nothing wrong with you, but others wrote that with young dandelion leaves Comfrey made a tasty spring salad.

John Gerard (1545 - 1612) reminds us how bawdy those times could be when he recommends:

“The slimie substance of the roote made in a posset of ale, and given to drinke against the paine in the backe, gotten by any violent motion, as wrestling, or over much use of women […]”

In Irish medicinal folklore Comfrey was used to drive away the worms that caused boils and thrived inside them. It was said that worms detested the smell of Comfrey and that a Comfrey based ointment would get rid of your worms and give you a lovely complexion.

They were on to something though: we now know that Comfrey contains Allantoin, which today is still used in medicinal creams and cosmetics. It moisturises and aids healing by increasing skin cell turnover while soothing any irritation.

In other languages the names for Comfrey also refer to either the mending of bones or the strange substance of the dark roots: ‘Smeerwortel’ in Dutch (Smear Root) and Beinwell in German (Bone heal). It’s Consoude in French, from the Latin word ‘Consolidare’, making solid. The same word is used in Italian, Consolidare and Consuelde in Spanish.

Other English names for Comfrey mostly refer to the healing of bones or the consistency of the black roots too: Knitbone, Knitback. Boneset, Banwort (Bonewort), Consound, Blackwort, Bruisewort, Slippery Root, Gum Plant, Consolida, Ass Ear (after the shape of the leaves) and Pigweed, (it’s been used as food for pigs, to keep them healthy and to keep them from being hexed by witches - very useful indeed.)

Flowerology is a reader supported publication. To support my work you might consider to subscribe for free, buy me a tea (to keep me awake when reading ancient herbals till deep in the night) or simply click the heart shaped ‘like’ button on the top or bottom of this post (it helps the algorithms apparently). Thank you!

If you’re curious about other wildflower names, you can find all flowers covered in Flowerology so far, in the alphabetical archive. And you can find a list of all the books used for researching Flowerology in the Reading List which is frequently updated with new etymology dictionaries, herbals and plant lore books.

This newsletter is NOT a field guide for flower identification. It’s often difficult to tell the difference between harmless plants and poisonous plants and some flowers are rare and protected by law, so, NEVER pick or use any plants or flowers if you’re not sure about them.

illustrations and text ©Chantal Bourgonje

*The real Apuleius, Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (124AD - circa 170AD) was a Numidian-Roman poet and Platonist philosopher, who lived in the area that is now known as Algeria. He was a famous orator and novelist and was NOT a herbalist or botanist. However, the mysterious writer and illustrator of the 4th century Herbarium tried to give his or her work a sense of gravity by claiming it was written by the famous author. This was not an uncommon practice in the early Middle Ages. An early form of identity theft?

This plant is the dragon plant of plants! I make either a poultice or a salve. You can even feel the initial 'knitting' when applied to sprained ankles to chapped lips. thanks for writing about this amazing plant. I really enjoyed your tribute.

I came across your work today and I am feeling SO GRATEFUL! Thank you for all the time and effort you’ve put into what is clearly a publication full of little treasures I get to experience again and again as I encounter the plants in the wild!