Betony

Stachys officinalis

Betony is one of those flowers that’s useful to have in your pocket when you are on your way home from the pub and happen to come upon a mad dog and some adders.

As John Gerard (1545-1612) wrote in his herbal:

“It is a remedy against the bitings of mad dogs and venomous serpents, [and] being drunk.”

Gerard also wrote that:

“It prevails against sour belchings. It makes a man to pisse well”

So it can also come in handy when you’ve overdone the pickled eggs or if you have a prostate issue.

But how did it come by its name? According to Pliny (23-79AD), it’s named after a nomadic, sheep-herding tribe from Spain, the Vettones, who discovered Betony’s many healing powers. And many healing powers it has: Twenty nine remedies alone are listed in the 10th century “Bald’s Leech Book”. Robert Turner, the 17th century Herbalist, Astrologist and Translator of ancient occult works, counted 30 illnesses it could cure in the various medieval manuscripts he worked with. And Antonius Musa (63BC-14AD), botanist and physician to Emperor Augustus went even further, claiming it could cure 47 diseases. There can’t be many herbs with more extensive curative powers.

Over time, and with a gentle variation in pronunciation, the Vetony herb became Betony.

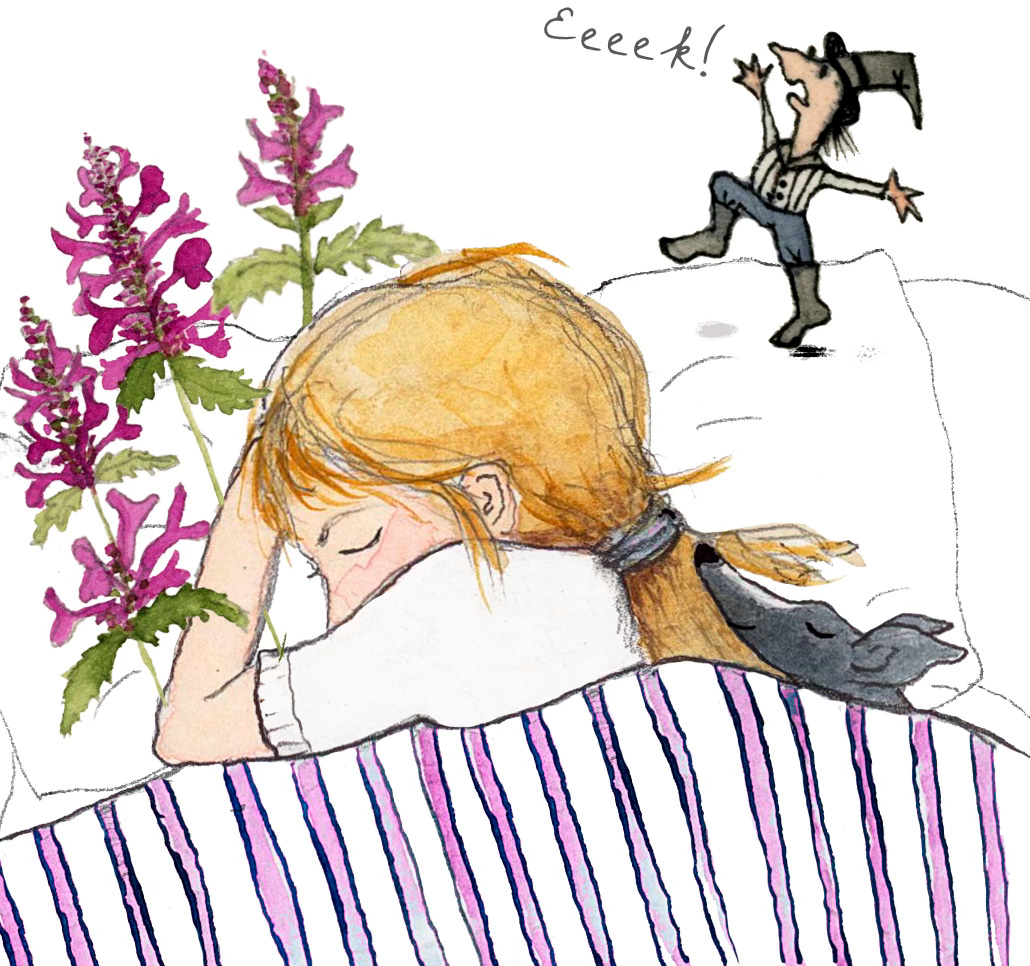

But it wasn’t just a medicinal herb, Betony was also said to ward off demons and “monstrous nocturnal visitors” (Bald’s Leech Book) - but only if harvested in August and without the use of iron tools.

It was also planted in church yards to ward off evil spirits. And Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) polymath and saint, wrote, it could sort out the possessed and those

“deceived by magic art […] and diabolic incantations”

Maud Grieve wrote in her “A Modern Herbal” (1931), that Erasmus (1466-1536) Dutch humanist and philosopher, claimed that wearing Betony amulets could prevent:

“Fearful visions” and was effective in “Driving away devils and despair.”

A medieval anti-depressant?

Betony was also claimed in “The Grete Herball” of 1526, and by Hildegard von Bingen, to be a cure for madness. Hildegard’s cure involves soaking your chest with Betony juice over night. I can’t help thinking you might need to be just a little bit mad to try it. But then the same could be said of a snake bite preventative, the recipe for which was given in the 4th century by Pseudo-Apuleius: a salve made of Betony, Hog-Fennel, deer grease and vinegar to be rubbed all over the body. If you’d forgotten to apply the salve before going out into the snake-infested fields, you could also apply the salve to the adder bite after the event to heal the poisoned wound.

It wasn’t just human beings who were said to know about Betony’s cures. It was believed that ‘wilde dēor’1 (wild animals) knew of Betony’s healing powers too. For instance, it was thought that deer, when shot with a hunter’s arrow, knew to eat Betony to heal the wound.

Derivation of the scientific name: ’Stachys’ comes from Greek and means ‘ear of corn’. The ear is the spike around which the flowers grow. Here it refers to the flower heads growing around the stem, in a vaguely similar way to an ear of corn. You need quite a bit of imagination to see this though!

‘Officinalis’ is the word for a monastery’s storeroom for plants of medicinal and culinary use, in other words: your medicine cabinet.

Other names are: Bishop’s Wort, Bidny or Bitny, Kestron, Wild Hop, Wood Betony, St. Bridget’s Comb, Common Hedge-nettle

Flowerology is a reader supported publication. To support my work you might consider to subscribe for free, buy me a tea (to keep me awake when reading ancient herbals till deep in the night) or simply click the heart shaped ‘like’ button on the top or bottom of this post (it helps the algorithms apparently). Thank you!

If you’re curious about other wildflower names, you can find all flowers covered so far in Flowerology in the alphabetical archive. And you can find a list of all the books used for researching Flowerology in the Reading List which is frequently updated with new etymology dictionaries, herbals and plant lore books.

This newsletter is NOT a field guide for flower identification. It’s often difficult to tell the difference between harmless plants and poisonous plants and some flowers are rare and protected by law, so, NEVER pick or use any plants or flowers if you’re not sure about them.

illustrations and text ©Chantal Bourgonje

Interestingly in Old English the word ‘dēor’ was the word for any wild animal. In other languages like Dutch and German, we still use the word ‘dier’ and ‘Tier’ respectively for ‘animal’. In Late Middle English however, the word ‘dēor’ became the word for ‘deer’. Before that, the Anglo-Saxons called what we now call a deer, a ‘heorte’ - ‘heart’. Think for example of The White Heart, referring to white stags. In Holland, the word for deer is ‘hert’. An intriguing intermingling of words.

This is such a sweet Substack. Without googling Betony, the artwork looks like it could be salvia. I’m off to google😂🌸

Bedankt weer voor de leuke interessante weetjes.